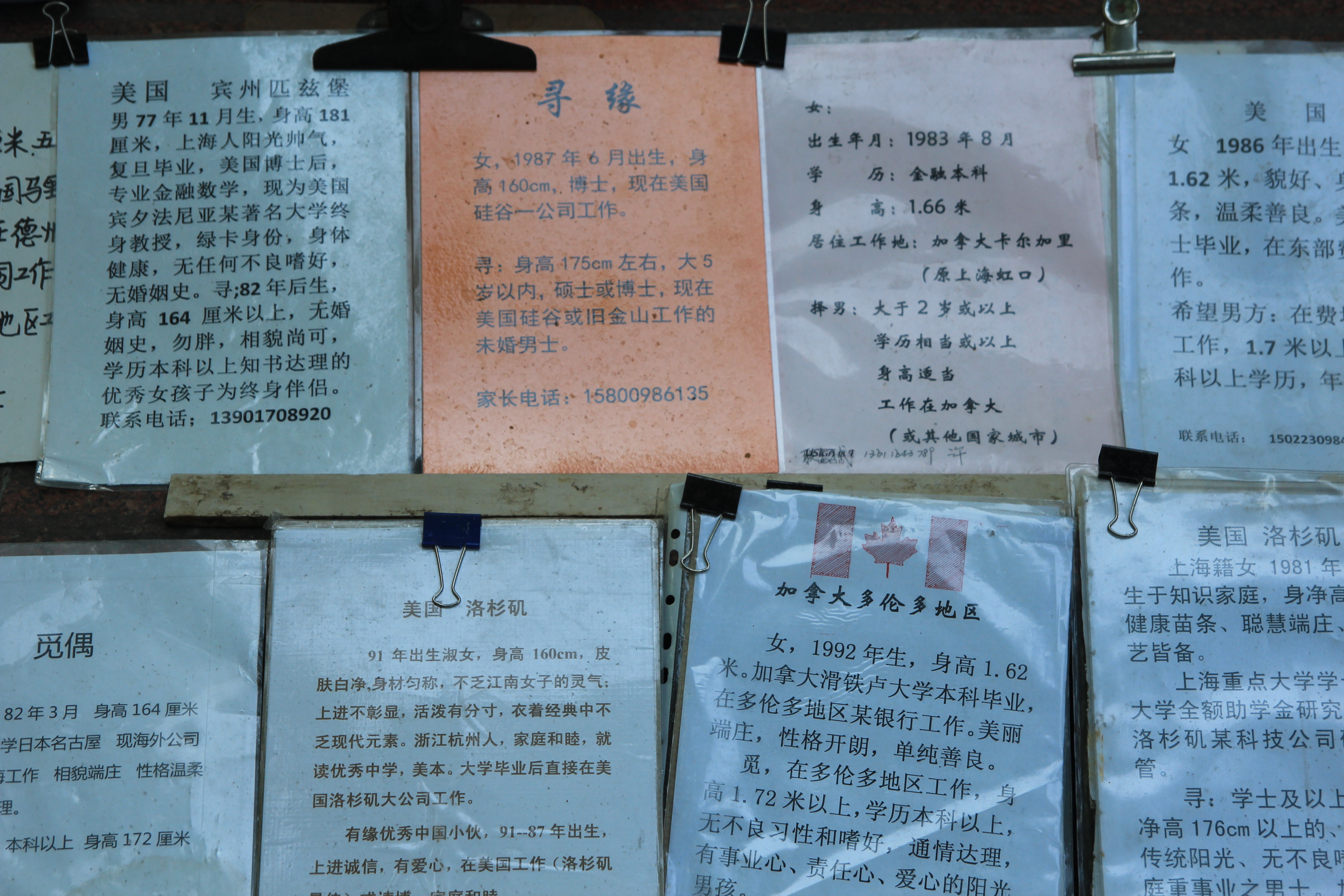

(Personal ads are posted on umbrellas in the marriage market in Shanghai’s People’s Park. Image: Peiqi Teh/Shutterstock)

Have you ever been set up on a blind date by a parent? How about a grandparent? For many young, single Chinese people, it’s an uncomfortable scenario that plays out again and again at China’s so-called “marriage markets” (相亲角 xiāngqīn jiǎo).

Marriage markets--perhaps more accurately called “matchmaking corners,” since no money is exchanged--are public spaces where parents (and sometimes grandparents) congregate to scout out potential spouses for their unmarried children. Many young Chinese people feel like they are too busy with school or work to date, while others simply haven’t had success in the romance department. Sometimes, that’s when their anxious parents take matters into their own hands.

Typically, parents post sheets of paper detailing their child’s eligibility as a potential spouse and the qualities a prospective son- or daughter-in-law should have. They often tape these personal advertisements to umbrellas, which serve as makeshift stands. Then, they chat with other parents to arrange blind dates between their children, and hope that sparks fly. It’s very rare to see anyone advertising him- or herself.

Though the whole idea might seem anachronistic, marriage markets are actually a relatively recent phenomenon. China’s first and largest marriage market, held on Saturdays and Sundays in Shanghai’s People’s Park, arose organically in 2004 as older generations met in the park to socialize. When the conversation inevitably turned to their children’s inability to find spouses, the marriage market was born. Now, marriage markets can be found in most major cities, and sometimes attract famous visitors.

So what makes someone a good catch?

Age

A 2018 survey (link in Chinese) of advertisements in the Shanghai Marriage Market showed that the vast majority of advertisements were for people aged 25-30. When stating their preferences for potential spouses, the majority of men were seeking younger women, while women preferred someone closer to their own age.

A severe gender imbalance--a byproduct of the now defunct one-child policy--is making it difficult for men to find wives. By 2020, an estimated 24 million Chinese men will be 光棍 (guānggùn, lit. “bare branches”), or bachelors. Despite this, most advertisements in the Shanghai Marriage Market were about women, which speaks to the deep anxiety felt by parents of unmarried daughters approaching the “ripe old age” of 30. Women who remain unmarried in their late twenties and beyond, often despite high incomes and educational attainment, are stigmatized as 剩女 (shèngnǚ, “leftover” women), and are even blamed for having overly high standards.

Zodiac Year & Astrological Sign

Curiously, it’s not uncommon to see advertisements that list requirements relating to the Chinese zodiac year and Western astrological sign of potential partners. Traditionally, people born in different zodiac years were thought to possess certain personality characteristics that made them more or less compatible with those belonging to different animal signs. Even today, some Chinese people still consult both Chinese astrology for guidance in love and marriage, and Western astrology is becoming popular too.

Household Registration

(Personal ads for Shanghai natives living overseas in the United States and Canada. Image: Peiqi Teh/Shutterstock)

Just as important as a potential partner’s birthdate is his or her birthplace--or rather, the location of his or her household registration (户口, hùkǒu). An urban hukou is considered more advantageous than a rural one, since it confers access to better social welfare benefits like education, housing benefits, and unemployment and medical subsidies. In major cities like Beijing and Shanghai, where obtaining a local hukou is extremely difficult, marriage can provide a shortcut, and any children resulting from the marriage can inherit either of their parents’ hukou. Thus, urban hukou holders have a bit of a leg up in marriage markets.

Job & Education

Historically, the concept of 门当户对 (mén dāng hù duì) was an important principle for choosing a spouse--that is, matches between individuals from households of equal social and economic standing resulted in the best marriages. While parents no longer arrange marriages for their children in the traditional way, marriage is still very much a family affair as well as an individual matter in contemporary China, and the concept of being well-matched in terms of income and educational attainment is still given weight.

Job and education are two of the essential pieces of personal information every advertisement lists. The candidates in marriage markets are by no means desperate: the 2018 survey of the Shanghai Marriage Market found that the dating pool was highly educated, with two thirds of both men and women having attained a bachelor’s degree or higher. Among those who stated an educational qualification for potential spouses, a majority of women were seeking a partner with a similar level of education, while men preferred slightly less accomplished partners.

But individual circumstances aren’t the only thing that matters. Many advertisements explicitly list a preference for people with similar family backgrounds, and it’s not uncommon for advertisements to list the white-collar occupations of one’s parents.

Ownership of Significant Assets

In the minds of many Chinese people, a man should be able to provide a car and a house before getting married. In the face of skyrocketing housing prices and fierce competition for jobs, this places a heavy burden on young men, many of whom push off marriage until they have saved enough. Those who do own their own car and house are considered more desirable than those who don’t, so marriage market advertisements often highlight asset ownership.

“Naked marriages” (裸婚, luǒhūn) are growing in popularity among younger generations. Unable to afford a car or house, many couples are choosing to get married anyway, often without a ceremony, in a rejection of what they view as outdated materialist values.

Appearance

While appearance is important, it isn’t the deciding factor. Many advertisements don’t include a photo, and those that do are often viewed with skepticism given the pervasiveness of photo-editing apps like Meitu.

Finding Love at the Marriage Market

(Not a millennial in sight. Image: Peiqi Teh/Shutterstock)

So how many blind dates arranged at marriage markets actually blossom into romance? It’s hard to say. There isn’t an official tally, but anecdotal evidence suggests successful matches are few and far between. Some parents advertise their children without their permission or knowledge, which, as you might imagine, does not always go over so well. And those couples who do meet and hit it off might not want to be open about where they met, just as many American couples feel embarrassed about meeting through a dating app.

Still, marriage markets do serve one very important purpose: letting parents vent their anxieties while singing the praises of their kids.

Want to learn more about love and family in contemporary China? Check out Reading into a New China.

Comments