The New Year (お正月 Oshōgatsu) is the most celebrated holiday in Japan. Preparation for New Year’s Day (元日 Ganjitsu) begins weeks before, as people rush to clean and decorate the house, prepare special foods, throw parties, and write greeting cards. Many businesses close for several days while families and friends gather to ring in the New Year on January 1. By the time Japan’s neighbors in Asia begin their own New Year’s celebrations in late January or February, the festivities in Japan are long over.

Japan is one of the few countries in East Asia that doesn’t celebrate the Lunar New Year, one of the world’s largest celebrations. This major holiday is known by many names (the Spring Festival in Chinese, Seollal in Korean, Tsaagan Sar in Mongolian, Tết in Vietnamese) and is observed in some shape or form by Mainland China, Taiwan, Singapore, Malaysia, Indonesia, Korea, Vietnam, and Mongolia--not to mention the Chinese, Korean, and Vietnamese diasporas worldwide.

So why doesn’t Japan celebrate the Lunar New Year along with its neighbors?

Japan Used to Celebrate the Lunar New Year

(A visit to a local temple on New Year’s Day. Image: taka1022/Shutterstock.)

The Chinese lunisolar calendar was introduced to Japan in the sixth century CE, and it was the principal method of timekeeping in Japan until 1873. Prior to that, Japan shared its New Year’s Day with China, Korea, and Vietnam, celebrating on the second new moon following the winter solstice. So what changed?

Lunar No Longer

In 1873, as part of the Meiji Restoration, Japan adopted the Gregorian calendar to bring the country in line with the West. At that time, the prevailing attitude among many Japanese elites was that Asian practices were inferior to Western ones, and would hold Japan back unless they were abandoned.

But when the Meiji government decided to adopt the Gregorian calendar, they simply superimposed lunisolar calendar events onto the new calendar instead of properly converting the dates. Thus, Ganjitsu, the first day of the lunisolar calendar year, fell on January 1, the first day of the Gregorian calendar year, creating a one month delay between Japan’s New Year’s celebrations and those of its neighbors like China and Korea.

In contrast, China adopted a dual-calendar policy in 1912, whereby the Gregorian calendar was used for everything except setting traditional holidays, which were timed according to the Chinese lunisolar calendar. Today, Mainland China, Taiwan, Singapore, Malaysia, Indonesia, and Vietnam all use similar systems.

(Men pound glutinous rice flour into mochi, a traditional food eaten during the New Year. Image: VANESSAL/Shutterstock.)

The decree abolishing the lunisolar calendar was issued so suddenly that the general public was left scrambling to get ready for the New Year. According to writer Asano Baidō (1816-1880), “There was no time to make year-end rice cakes, so one had to buy New Year rice cakes at the rice cake shop. Some people put up the kadomatsu [a traditional decoration made of bamboo and pine] on the second day of the Twelfth Month and some didn’t put it up at all…”

Initially, opposition to the change was strong, and many people continued to celebrate the Lunar New Year well into the 1900s, especially in rural areas. Eventually, however, the lunisolar calendar faded completely from daily life in Japan.

That is, almost completely. Today, there are still traces of Japan’s Lunar New Year celebrations, if you know where to look.

Ōmisoka: “The Great Thirtieth Day”

(New Year’s Eve fireworks display over Tokyo Bay. Image: onotorono/Shutterstock.)

In Japanese, New Year’s Eve is known as 大晦日 (Ōmisoka). 晦 (miso) was originally written as 三十 (30), referring to the last day of the lunisolar month (usually the 30th), and the 大 (Ō) indicates that it is the final last day of the month for the year. So today, even though New Year’s Eve is always celebrated on December 31, the holiday is still known as “the great thirtieth day”!

Koshōgatsu: Little New Year

(Azukigayu is not only a traditional meal, but a divination tool, too! Image: Shutterstock.)

In Japan, January 15 is known as 小正月 (Koshōgatsu), or “Little New Year.” Before Japan adopted the Gregorian calendar, Koshōgatsu always coincided with the first full moon of the new year, falling on the same day as the Chinese Lantern Festival. Historically, it was a day to pray for a bountiful harvest. For breakfast, it was customary to eat 小豆粥 (azukigayu), rice porridge with sweet, red azuki beans. A divination ritual was then performed by placing bamboo cylinders in the remaining porridge and leaving them overnight. The more rice that was stuck inside the cylinders the following morning, the better the harvest would be that year.

Today, many families still eat azukigayu on January 15, and some temples and shrines still perform the traditional divination rituals. Koshōgatsu is also the day when New Year’s decorations are taken down, and in some places, used decorations are burned in special bonfires!

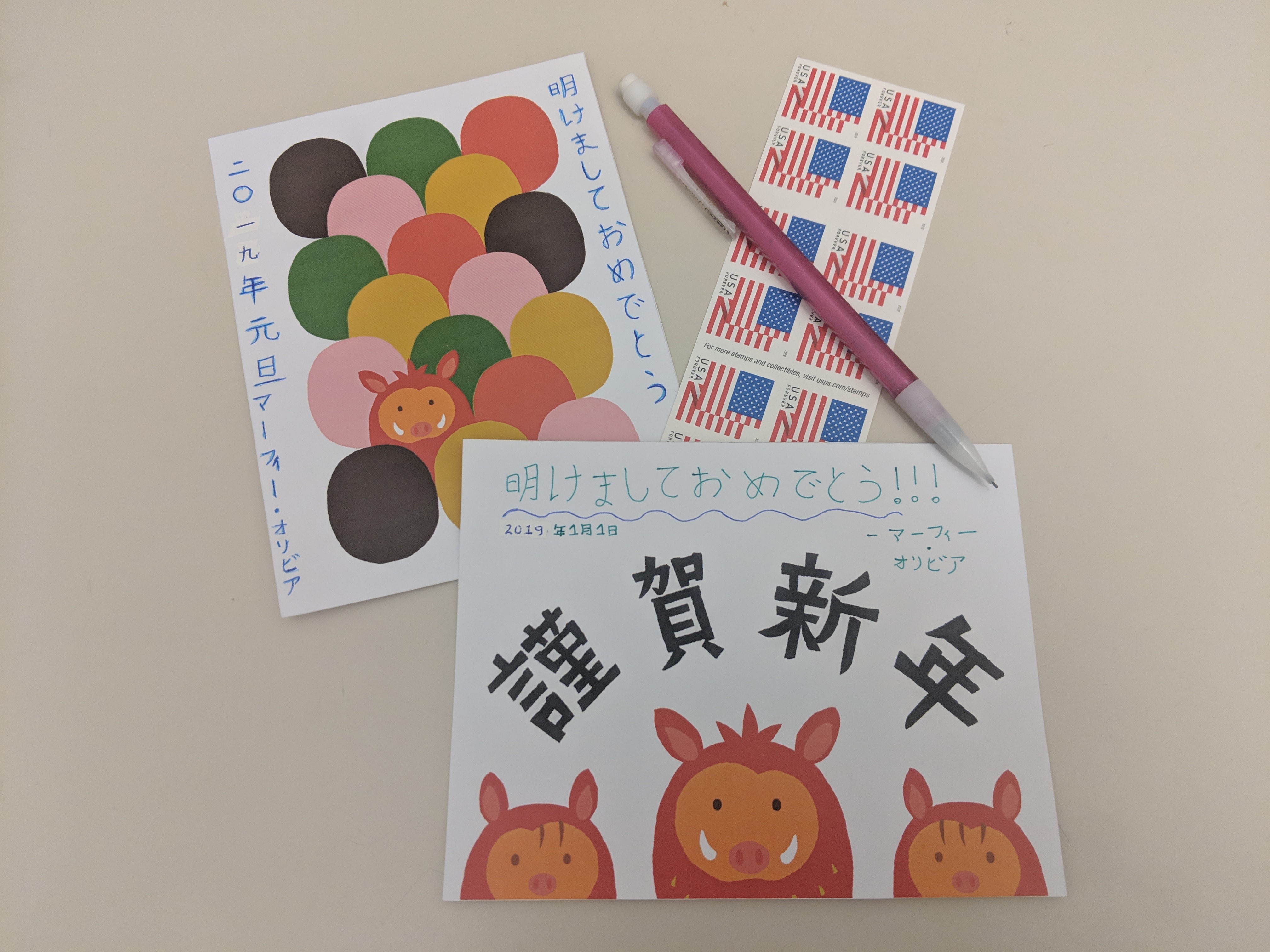

Nengajō: New Year’s Greeting Cards

年賀状 (nengajō) are New Year’s greeting cards that are sent to friends, relatives, teachers, and colleagues, and are delivered in the mail on January 1. The Japan Post still prints about 3 billion nengajō every year, though this number is declining with the recent digitization of cards.

Though Japanese New Year no longer coincides with the Chinese Spring Festival, Japan still uses a 12-year zodiac that is very similar to the Chinese zodiac, and many nengajō feature the New Year’s zodiac animal. In 2019, Japan will celebrate the Year of the Boar.

To get into the New Year’s spirit, why not celebrate by sending nengajō of your own? Write your New Year’s greeting, the date, and your signature on the front of the postcard, and don’t forget to include your address and the recipient’s address on the back. If you don’t feel like making your own, you can download one of our pre-made postcards below!

If you’re reading this before midnight on December 31st,

よいお年をお迎えください! Have a good year!

If you’re reading this on or after January 1st,

あけましておめでとうございます! Happy New Year!

Comments